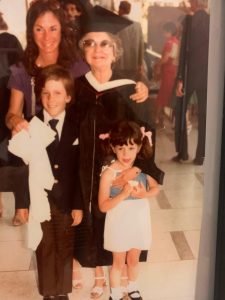

my mother’s college graduation, 1981- she is 63

My six-year-old daughter, Rachel and I were shopping for a gift for my mother’s sixty-third birthday.

Rachel spotted a small velvet throw pillow trimmed in royal blue.

“Do you think Grandma would like that?”

Royal blue is my mother’s favorite color, but it’s the words stitched in pale blue wool that stand out:

“Mirror, mirror, on the wall, I am my mother after all.”

I’d vowed to mother my own children differently from the way I’d been mothered, unaware that we are unconsciously wired by our early childhood experiences. It would take me a long time to understand that even with hard work on ourselves, we are all prisoners prone to repeat the past. I had no way of knowing I would inadvertently follow in my mother’s footsteps, more than once.

***

Four years earlier, it had been a hot and humid August day on Long Island, and I was sitting on the beach with my mother and Rachel, who was two, when my old college friend Barbara arrived, escaping the heat wave suffocating Manhattan. Sheltered by a huge umbrella, Rachel was engrossed, digging in the sand. Barbara was recently divorced, and I hadn’t seen her in almost a year. I was itching for a few moments of privacy to catch up and hear how life was unfolding for her. When Barbara suggested the two of us take a walk on the beach my mother agreed to watch Rachel.

“Just sneak away when she’s busy,” she whispered. “If you tell her you’re leaving, she’ll probably have a tantrum. If you just take off, she’ll never even know you’re gone.”

Something inside me rumbled. I should have listened to my body, but instead of following my gut, I stood up quietly and snuck off with Barbara. I couldn’t have been more than fifty feet away when I looked back to see how Rachel was doing. There she was, sitting on my mother’s lap, screaming. Leaving Barbara at the water’s edge, I turned and raced back to my daughter. As I neared, she spotted me and flew out of my mother’s arms and into mine.

“Mommy,” she wailed, as we sat on the scorching sand, “where were you? Why didn’t you tell me you were going away?” I hugged my screaming girl, dried her tears, and settled her down. Then I looked over at my mother.

“I shouldn’t have walked away without telling her where I was going.” I added, “That’s not the right thing to do, Ma.”

“Don’t worry,” my mother said. “She’ll get over it. You used to scream bloody murder when I left you.”

It took me a minute to absorb what she had said. “I screamed bloody murder when you left me,” I repeated. “So, if you knew she’d be so upset, why did you tell me to sneak away?”

My mother shrugged. “I knew you wanted to take a walk with Barbara, and I knew she’d get over it. She’ll get over it, dear; we get over everything, dear. You certainly did. Don’t worry so much. She’ll be fine.”

My mother had capped off her speech with her signature lines: “She’ll get over it. We all get over everything. She’ll be fine.” Sitting there, glaring at my mother and rocking my daughter, I bit my lip so as not to explode. What kind of horrible advice had I gotten from my mother, once again? But not only was I angry with her, I was livid at myself, critical and ashamed of my poor judgment. By the time I left Rachel on the beach that sticky August day, I was already familiar with my mother’s cavalier child-rearing philosophy. Years of my own psychoanalysis had unearthed the childhood roots of my insecurities. I had even come to understand that my mother had never meant to be harmful.

She’d done the best she could, and, as she described it, she was simply a product—or a victim—of her generation. But my frustration ran deeper than my anger at my mother. In addition to ignoring what I’d learned from my own therapy, I was now a graduate student studying psychology, drenched in child-development theories, which across the board stressed the importance of parents’ creating a secure attachment as a prerequisite for healthy growth. Nonetheless, I had ignored my instincts and listened to my mother. In essence, although I’d sworn never to be like her, I had blithely and blindly followed in her footsteps.

While my life work as a therapist certainly supports my belief that growth and change are always possible, two caveats should be noted. Without hard work on ourselves, we are doomed to repeat the past, and, even when we do our difficult inner work, the road to reconstructing oneself is bumpy, filled with unexpected potholes. It’s taken me decades to understand the limitations of psychological insight and to respect the fact that insight can be hijacked so easily by our early programming. And my early programming—true for most of us—is not what I learned in my twenties as a psychotherapy patient or in my thirties as a graduate student, but rather what I learned as a small child who yearned for my mother’s love and approval. Driven to please her, I absorbed and internalized her essence. Unconsciously, a part of me was still devoted to the voice in my head whispering,

“Mother knows best.”